Oxcarts in Costa Rica were simple, functional, plain wood until Joaquin Chaverri transformed his cart into a raucous explosion of colors to liven up his family’s Sunday outings. Find out more on the story behind the tradition of oxcarts in Costa Rica.

Article by Shannon Farley

There is perhaps nothing as emblematic of Costa Rican culture as the colorfully-painted wooden oxcart, its team of matched oxen, and their oxcart driver.

Once the main form of transportation across the mountainous country that depended on agriculture for its survival, oxcarts (called carretas in Spanish) today are mostly used for celebrations and are considered one of the traditional and cultural icons for Costa Rica.

On March 22, 1988, the oxcart was designated the National Labor Symbol for Costa Rica. In 2005, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) proclaimed Costa Rica’s vibrantly painted, traditional oxcarts to be an Intangible World Cultural Heritage.

Oxcarts are not only used in Costa Rica but in many rural areas around the world. However, Costa Rican oxcarts are famous for their unique and colorful painted designs on the cart, wheels and oxen yoke that include geometric patterns, flowers, animals, landscapes, and even sometimes portraits. No two oxcarts are painted exactly the same. The fine art of oxcart painting has been passed down in families from generation to generation, especially in the Central Valley town of Sarchi – located west of San Jose.

But it wasn’t always this way.

How Oxcarts in Costa Rica Got Their Colors

Originally, Spanish colonizers to Costa Rica brought oxcarts to be used for transportation and farm work. But their original European design of spoked wheels kept getting stuck and breaking in the rugged, muddy Costa Rican terrain. So, during the mid-19th century, a new design based on the indigenous Aztec disc was incorporated into a solid wood wheel bound by a metal ring that could cut through mud without getting stuck.

Dating from about 1840, oxcarts were used to transport coffee beans, sugar cane, corn and other goods from Costa Rica’s Central Valley over the mountains to the Pacific Coast port of Puntarenas or the Caribbean port of Limon for export. The journey would take 10 to 20 days crossing jungle-covered mountains, rivers, swamps and beaches. Now you can drive that same route in a little over an hour to the Pacific and in about two hours to the Caribbean.

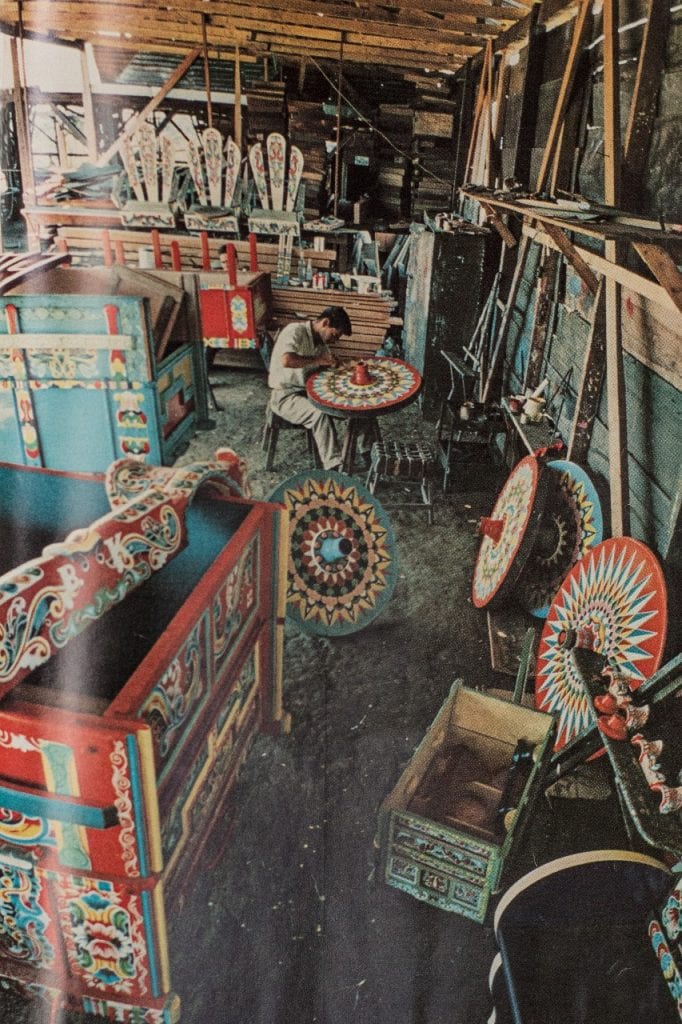

The earliest oxcarts were simple and functional plain wood. The tradition of painting and decorating oxcarts started in the early 20th century at the Joaquin Chaverri Oxcart Factory, which began in 1902 in the artisan town of Sarchi. Farms near Sarchi have been producing some of the country’s best coffee beans for over 100 years. The demand for oxen-pulled carts was born of the need for a sturdy way to transport this precious cargo to the coastal ports.

The story, handed down in the family of Joaquin Chaverri, says that Joaquin decided to beautify his oxcart to take his family on outings in the cart on Sundays. He painted his first oxcart bright orange because that was the only color he had available, according to his family. Orange and red have since become known as the most traditional colors for cart painting. Joaquin used powdered pigment mixed with linseed oil to deeply soak into the wood, making it more durable and long-lasting.

The designs and colors in the decorations are based on Costa Rican plants and flowers. Curlicues, for instance, are modeled after chayote (squash) and ayote (pumpkin) vines. The iconic star shapes on the wheels were inspired by spear tips. The Chaverri family tells that Joaquin wanted the designs to be different from any other kind of art at the time. Not having any ready-made brushes, he fashioned them from dogs’ hair.

When the practice of painting oxcarts spread, different regions – and sometimes even individual families – developed their own particular design and color scheme. At one time, it was said that you could tell where a farmer was from just by looking at how his oxcart was painted.

Oftentimes, oxcarts were a family’s only means of transport, and they served as a symbol of social status. Very elaborately painted carts meant the owner was wealthy and had the money to pay a talented painter. Each oxcart also was designed to make its own “music,” a unique chime produced by a metal ring striking the hubnut of the wheel as the cart bumped along.

Once the oxcart became a source of pride for people, greater care was taken when crafting them like selecting the highest-quality wood. Eventually, contests were held to award the “most creative and inspiring oxcart designs” – a practice that continues today.

Costa Rican Oxcarts in Modern Times

Although trucks, tractors and other motorized vehicles have mostly replaced oxcarts in everyday life, some farmers still stick to the old ways by using them during harvest season or when places are too rough for modern vehicles. Oxcarts remain strong symbols of Costa Rica’s rural past and still feature prominently in parades, festivals, and other celebrations. You can see the “World’s Largest Oxcart” – built in 2006 – in the Central Park in Sarchi.

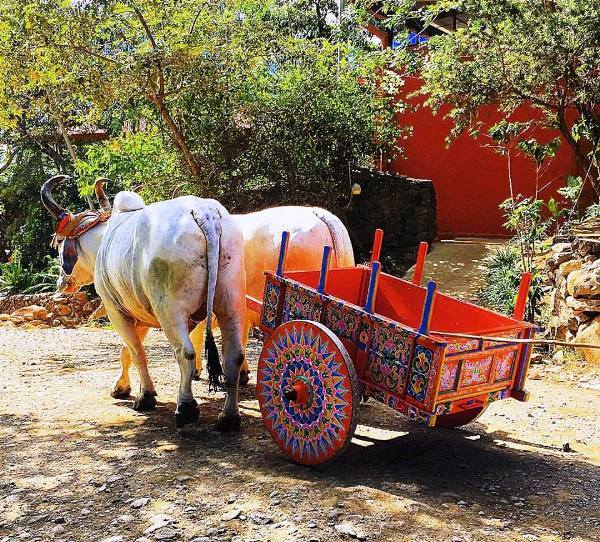

At the 138-year-old Guanacaste ranch of Hacienda Guachipelin, now an award-winning Costa Rica eco-hotel, their oxcart comes from the famous Joaquin Chaverri Oxcart Factory in Sarchi. Painted in traditional orange with rich decorations, the hotel’s oxcart is just one of the many symbols of Costa Rica’s rich ranching traditions at Hacienda Guachipelin.

You can experience these traditions in person when you visit Hacienda Guachipelin. There are cowboy shows every Saturday, and the oxcart passes by the hotel’s Adventure Center daily at noon for photographs with visitors.