A 1917 natural history book reveals a forgotten travelogue about the Hacienda Guachipelin ranch and life in the wild tropics of Costa Rica at the beginning of the 20th century.

Article by Shannon Farley

Discovering old historic documents about a place is like finding hidden treasure in a forgotten attic or cellar.

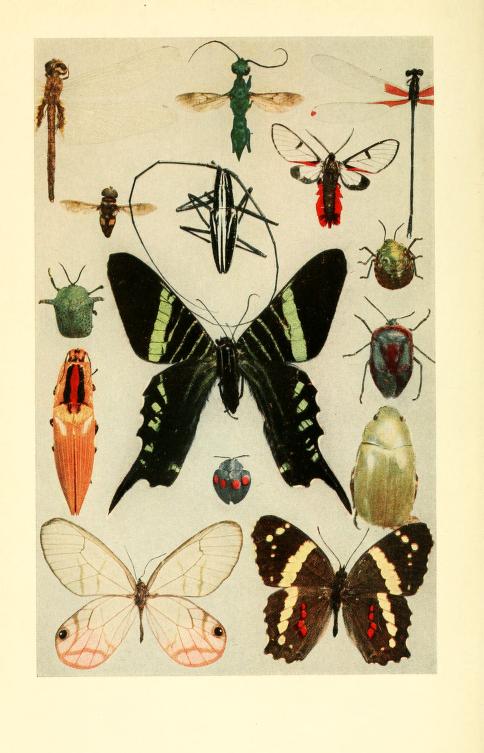

That’s how it was for Jose Tomas Batalla, owner of Hotel Hacienda Guachipelin, when a colleague sent him the online link to a 1917 book entitled A Year of Costa Rican Natural History. Written by the husband and wife scientific team of Amelia Smith Calvert, sometime Fellow in Biology from Bryn Mawr College, and Philip Powell Calvert, Professor of Zoology at the University of Pennsylvania and Editor of Entomological News, the 577-page book describes a long account of the Calverts’ travels and observations of nature in Costa Rica including a visit to Hacienda Guachipelin in Guanacaste.

The original book is housed at the Brown University Library in Providence, Rhode Island. It was first published by the Macmillan Company in February 1917, and the Calverts’ trip and research happened between 1909 and 1910.

Their account is wonderfully detailed – starting with their arrival by steamer ship to the Caribbean Port of Limon, and their journey across Costa Rica to Cartago, Volcano Irazu, San Jose, Volcano Poas, Puntarenas and the Guanacaste region, among many other places.

Their account is wonderfully detailed – starting with their arrival by steamer ship to the Caribbean Port of Limon, and their journey across Costa Rica to Cartago, Volcano Irazu, San Jose, Volcano Poas, Puntarenas and the Guanacaste region, among many other places.

“We arrived at Limon on the Hamburg-American steamer ‘Sarnia’ from New York on Saturday, May 1, 1909, and left for the United States by the ‘Prinz Joachim’ of the same line, on Monday, May 10, 1910. Between these two dates is comprised our year of Costa Rican Natural History,” the authors’ state in Chapter One.

Their purpose in Costa Rica was to study dragonflies and to see the effects of the Panama Canal (U.S. construction between 1904 and 1914) on nature in Central America.

“The completion of the Panama Canal and its use by the ships of all the world will have a profound effect on the countries near the Isthmus. Costa Rica, lying immediately north of Panama, with her high mountains, her rushing rivers, her great variety of climates and of natural products, will share in these transformations,” the book reads.

A foreshadowing of the tourism boom to happen 100 years later, the couple extols the virtues of traveling in Costa Rica.

“This little republic is so readily accessible, it is so easy for foreigners to travel there and it offers such wonderful inducements to naturalists and entomologists (for many of whom the time and expense involved in visiting most portions of the American tropics are absolutely prohibitive) that it certainly should be much better known than it is at present.”

In early January 1910, the Calverts traveled to Liberia, the largest city in Guanacaste. They wanted to explore by the Rincon de la Vieja Volcano and so planned a trip to the ranch of Hacienda Guachipelin, located at the foot of the volcano. Their journey by horseback gives a good glimpse into what life was like in Costa Rica at the time. The excerpt about Hacienda Guachipelin begins on page 431 and continues to page 442.

“… We therefore planned a trip to Hacienda Guachipelin … obtained permission from the owner of this farmhouse — Señor Elias Baldiocedo of Liberia — for us to stay there for a few days. The Governor detailed as a guide Luis Padilla, No. 237 of the Federal Police, in neat khaki uniform with dark blue cuffs and collar, and Señor Cortes supplied us with three horses. Taking only necessaries and collecting apparatus, we left Liberia at 2:35 P.M. on January 14, rode north along the Carretera Nacional (National Highway), fording the streams in the Quebradas de Panteon and Clara, crossing the Rio Santa Ines (river) by a wooden bridge and turned off from the Carretera (which continues to Nicaragua) to the right about 3:30 … We descended into the valley of the Rio Colorado (river) and reached its bank about four o’clock,” the authors write.

“From the valley of the Colorado we climbed up to a ridge which separates that river from the Rio Blanco and runs in a general northeasterly direction. At times the roadbed was of the same character as in the streets of Liberia and worn by the wheels of the ox-carts into two ruts often a foot or more deep; or the whole roadbed was worn down the width of an ox-cart two or three feet below the rock on either side,” the authors continue. “Human habitations of any kind were very few and far between after leaving the Carretera Nacional. Hacienda Guachipelin was said to be four hours distant from Liberia … we drew up at Hacienda Guachipelin at 6:35, four hours to the minute from Liberia. We received a hearty welcome from the mandador (caretaker), Genaro Espinoso, who was ever ready to do all he could for us during our stay.”

The researchers explained what it was like to stay at the Hacienda Guachipelin ranch, which dates back to 1880, showing that daily life was quite simple – bathing in a nearby brook, and dining on eggs, rice, black beans and tortillas.

“The Hacienda, which stood on the top of a small hill, was L-shaped, the inner angle of the L with a southerly exposure. Its walls were built of wide boards and the roof was partly of tiles, partly of corrugated galvanized iron. The front or south side had a veranda to which one ascended by some tumble-down tile steps; the floor of the veranda was likewise tiled while the house within had wooden floors … Every now and then a pig ran in at one door of our dining-room and out of the other; two cats regularly came to beg at our table at mealtime, but the three or four dogs were less frequent visitors.”

The couple and their guides explored the surrounding forest on foot and by horseback, collecting samples of insects and plants and trees. One day, they rode a few hours to the fumaroles at Rincon de la Vieja Volcano: “pools of warm or hot water, in the latter case bubbling and boiling, all more or less clouded with the white clay in which they lie.”

“At sunset I sat behind the Hacienda watching Cerro Guachipelin (Guachipelin Mountain), over which the easterly winds were constantly blowing great masses of clouds illuminated by the rays of the setting sun; the summit was never visible. Near the house, in line with the same cerro (mountain) and lower than where I sat, horses and cattle were grazing quietly in a green potrero (field). Very high up in the blue sky overhead swifts were circling as they do at home, while much below them, from tree top to tree top flew twittering green parakeets.”

Visit Hacienda Guachipelin and Rincon de la Vieja Volcano today

The exceptional location of Hacienda Guachipelin, bordering the Rincón de la Vieja National Park, has made it a top place to visit in Guanacaste for decades.

You can see today the same volcanic fumaroles, forest, streams and wildlife that the Calverts saw more than 100 years ago. Make your reservation here to stay at award-winning Hotel Hacienda Guachipelin.